This piece was originally published in Politico, here.

I sought safety. That was my destination. I wasn’t thinking of European cities or towns. I just wanted to be safe.

That’s why I left my country. It’s why I didn’t stop in those nearby either—I had to keep moving. First through Sudan and Libya, then on a wooden boat across the Mediterranean Sea, where I was eventually picked up by a rescue ship.

More than 10 years have passed since then, and I live in Italy now. But through my work, I find myself reliving that experience over and over.

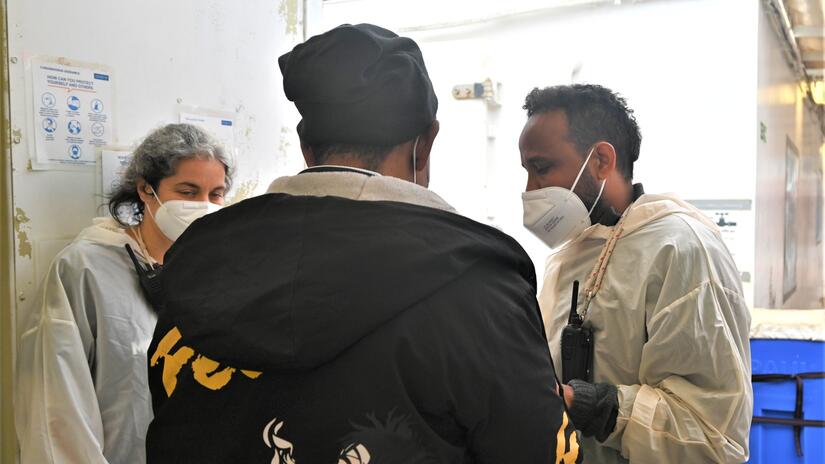

Abdel aboard the rescue ship Ocean Viking at dusk, wearing personal protective equipment, as he waits to help rescued people at sea.

Photo: IFRC/Alexia Webster

The most important part of my job is telling the people we rescue: “You are safe.” It’s as if I’m also telling their mothers, telling their brothers and sisters and all their villages too. I celebrate this moment with them; I celebrate their lives with them. Because too many others never get to hear those words.

In the last few months, we’ve seen tremendous solidarity with those fleeing the war in Ukraine; it is incredibly inspiring. Yet witnessing the overarching willingness to help victims of this crisis, while so many who flee suffering and persecution elsewhere end up at the bottom of the sea, raises the question: do human lives really carry such difference in value?

People rescued at sea sit together on board the Ocean Viking rescue ship in February 2022 as the ship's crew waited to be assigned a place of safety to safely disembark survivors.

Photo: IFRC/Claire Juchat

It was never my first choice to undertake such a dangerous journey to seek safety so far from home. But the lack of available legal channels to access international protection made it my only option — it was a necessity. And while states argue about migration policies and practices, for us volunteers, it is simply about saving lives and alleviating suffering.

When I left Eritrea 20 years ago, fleeing compulsory military service and forced labor programs, I didn't know where Europe was, what it was like or how to get there. It also didn’t occur to me that I was saying goodbye to my family, and my country, for the last time. Like my brothers and sisters in Ukraine today, my only concern was avoiding bullets. And I am one of the relatively few from my part of the world fortunate enough to reach a place of safety in the end.

When I was travelling through the desert in Libya, I remember seeing a group of people—women, men and children—lying crumpled on top of each other, naked. I asked the driver why they were naked, and he told me that their car had broken down and they had burned everything to try and attract attention, including their own clothes.

What is the use of clothing anyway, when one is facing death? They were just some unknown people, who came into the world naked and left naked. People so off the radar they had to burn everything in the hopes of being seen.

Still, even that was not enough.

SOS MEDITERRANEE rescue teams approach an overcrowded rubber boat in the Mediterranean in late March 2022. Teams brought people aboard the Ocean Viking ship as part of a 5-hour rescue operation during dangerous weather conditions. Two people had tragically lost their lives aboard the dinghy.

Photo: SOS MEDITERRANEE/Jeremie Lusseau

You meet merchants of death in Libya too—those who organize the trips to leave by boat, who are your only hope of escaping that hell. When you experience how horrible life there is—the prisons, torture, gangs and slave markets—you are not afraid of death, only of dying without trying.

When I finally reached the coast and went toward the waiting boat, I could barely walk from both the fear and hope. I saw mothers throwing their children onto the boat and following after them. I did not wonder why a mother would throw her child inside this small boat. I was sure that whatever she had seen must be more terrible than the sea and its darkness.

We set out at night. Eventually, the time comes when you can’t see anyone, not even yourself, but the prayers, crying and moaning remain. At that moment, the sounds of children are the only source of certainty that you are still alive.

We were at sea like this for three days until the rescue ship found us.

Abdel tends to a man called Haidar from Sudan who was rescued in the central Mediterranean by the Ocean Viking rescue ship in March 2022.

Photo: IFRC/Rita Nyaga

One might ask why someone decides to go through all this. But just look at what is happening in the countries people are coming from: the suffering caused by conflict, hunger, poverty, climate change and many other factors that are often present in their surrounding countries too.

And those who leave don’t just do it for themselves—they’re an investment for their families and communities. One of my friends sends the money he earns back home to build a school in his village. Another one has funded access to safe water. The money that migrants around the world send home is three times more than what comes from aid.

The Ukraine crisis and the response to it have now shown us what is possible when we put humanity first, when there is global solidarity and the will to assist and protect the most vulnerable. This must be extended to everyone in need, wherever they come from.

Nobody should have to experience what I have been through—in my own country, on my migration journey or when I arrived in Europe.

Everyone deserves to hear the words, “You’re safe.”